Introduction To Scales

Scales are the foundation of music. It literally means steps, the movement of one note to another. Simply put, it is the order of notes. Without it, music does not make sense. In the Western music tradition, there are 12 notes to represent all the musical pitches, and they are represented by the first 7 letters of the alphabet, i.e., A to G. After the note G, the note names will cycle back to A.

A-B♭-B-C-C♯-D-E♭-E-F-F♯-G-G♯

♯ = sharp

♭ = flat

Pitch

Sound is the result of the vibration of air molecules. The difference in vibration speed can be discerned by human ears. The speed of this vibration is what is known as audio frequency. It is measured in the standard unit, Hertz (Hz). Sound with low frequency produces low pitch, high frequency produces high pitch. For example, the open E string of the violin vibrates at 660Hz=660 vibration cycles per second, while the open E string of the double bass vibrates around 40Hz. The range of human hearing is around 20Hz to 20,000Hz.

If we observe how humans talk to each other, they do it in varying pitches which is also known as inflection, which helps them to articulate their intentions or feelings better. For example, they raise their pitch when they get excited, passionate, or agitated, but speak in a lower pitch when they feel morose, lethargic, or bored. Pitch plays an imperative role in music as it represents a wide gamut of human expression.

However, in contrast to human speech, a musical pitch, i.e., a note is clearly defined and locked to one frequency at a time. It does not fluctuate up and down. When the pitch goes up or down in a song, it does so by steps or leaps, instead of a glide. In this way, a note has a specific boundary that cannot be trespassed.

Octave Phenomenon: Where Do Pitches Come From?

Due to the inherent shape of the cochlea, our ears can “measure” pitch by applying mathematical ratios on the go. As a pitch moves up or down, we can somewhat feel that it moves in a cycle. When the frequency of a pitch is doubled or halved, we will arrive back to its origin, albeit in a higher or lower register. For example, if one pitch with a frequency of 220Hz and another of 440Hz sounded simultaneously, they would blend perfectly, as if only one frequency is sounded. This is known as an octave. In music, this is the most important interval, i.e., distance between two notes as it creates the boundary for all other pitches in between. Since these notes blend well together, the interval is also dubbed a perfect interval. By applying this frequency ratio of 2:1, we can create an octave of any stable pitch.

Nevertheless, music is definitely not just about having pitches that agree with each other. Across the spectrum of one pitch to its octave, there are pitches that complement and contradict. This is also known as consonance and dissonance, and this contrast makes music what it is. The first question is, how many pitches/notes should be assigned within an octave? The next question is, how far is the interval between one note to the next before it reaches its octave?

Apparently, these questions have been the subject of study for millennia, be it from musical, mathematical, spiritual or philosophical perspectives. Countless treatises have been presented; different cultures and different eras have used different formulae in the quest for defining what good music is. For example, Western music uses a scale of 7 notes, an Oriental/Chinese scale uses 5 notes, while Turkish Classical music has 53 notes. The science and art of dividing the pitches within a scale is called a tuning system or temperament.

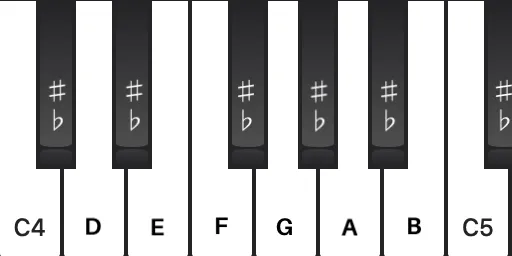

Anyhow, our focus here is only on the Western music scale, as it forms the bulk of today's music. In general, the octave is divided into 12 notes, and each note has an equal distance, i.e., interval to its neighbouring notes. This division of pitches is known as equal temperament. This temperament became the standard as it allows musicians to play in all keys without being out of tune in certain keys, unlike in other tuning systems of the past.

In equal temperament, the smallest interval is called a semitone. A note which is a semitone higher than the preceding note is called a sharp (♯), while a note which is a semitone lower than the preceding note is called a flat (♭). For example, if we move up one semitone from C, the note is C♯. If we move down one semitone from E, the note is E♭. The sharp or flat symbols added to a note are known as accidentals.

When we move up or down by two semitones from a note, the interval is called a tone. For example, if we move up one tone or two semitones from A, the note is B. If we move down one tone from G, the note is F.

N.B. 1 tone=2 semitones

A-B♭-B-C-C♯-D-E♭-E-F-F♯-G-G♯

If we look closely at the example above, when notes move up or down by a semitone, they alternate between natural notes (notes without accidentals) and sharp or flat notes. The exception goes to B and C, and E and F—these natural notes are a semitone apart. If we look at the keyboard of a piano, there is no black key between these notes.

N.B. Always remember that B and C and E and F are a semitone apart.

In this tuning system, notes can be played enharmonically, i.e., 2 different notes that share the same pitch. For example, an F♯ and G♭ are the exact same pitch, despite technically being different notes (this topic can be rather daunting for beginners so hopefully it can be discussed in future posts). Thus, for the time being, let's assume that the following notes are the same:

A♯=B♭

B♯=C

C♯=D♭

D♯=E♭

E♯=F

F♯=G♭

G♯=A♭

7 Notes To Rule Them All

However, only 7 notes are required in the common scales, i.e., major and minor. When notes outside of the scale are played, they will clash and produce unwanted dissonance in the music, unless it is intended by the composer. Thus we have to select and affix only the correct notes in a scale. The 1st note of each scale is called the key note. For example, if we pick the note A as the starting note, it will be called A major or A minor. In total, musicians need to master scales in 24 keys (12 major and 12 minor).

Scale Degree

Scales are all about knowing the right order. If we lay down the order of any major or minor scale, it can be illustrated as follows:

1-2-3-4-5-6-7-1* (going up/ascending)

1*-7-6-5-4-3-2-1 (going down/descending)

*This represents an octave, i.e., the 8th note, which is the same note as the starting note except higher in pitch.

Each note in the order is assigned to a function, also known as a scale degree.

1=Tonic

2=Supertonic

3=Mediant

4=Sub-dominant

5=Dominant

6=Sub-mediant

7=Leading tone

The same note in two different scales will have a different function. Let’s compare one note in two different scales according to its order. The following scales are C major and G major:

C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C

1-2-3-4-5-6-7-1

G-A-B-C-D-E-F♯-G

1-2-3-4-5-6-7-1

In C major scale, the note C is the 1st note, i.e., tonic while in G major scale, it is the 4th note, i.e., subdominant. In the given Audio examples, the accented note indicates the note C. Thus, besides knowing the right notes in any particular scale, musicians also need to know their position within that scale.

N.B. A musical accent (>) is when a note is emphasised by playing it louder than usual.

Major Scale

In any major scale, we need 7 notes plus the octave (1st). Take note that the interval (distance between two notes) of the 3rd and 4th note, and the 7th and the octave (1st) must be one semitone. The remainder of the notes are all one tone (two semitones) apart. Let's take a look at the scale of C major.

C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C

1-2-3-4-5-6-7-1

E and F are the 3rd and 4th notes while B and C are the 7th and the octave, hence the interval between these notes must be a semitone. In the given Audio example, these notes are indicated with accents.

N.B. Always remember this rule: 3 and 4 and 7 and 1 must always be a semitone in a major scale.

Minor Scale

A minor scale is slightly more complex than a major scale since it has three forms: natural minor, harmonic minor, and melodic minor. To simplify matters, what differentiates between a major and minor scale is the 3rd note. In all forms of minor scales, the 3rd note is always flat (♭). Now, let's compare the differences between the three forms of minor scales in the key note of C.

C natural minor

C-D-E♭-F-G-A♭-B♭-C

1-2-♭3-4-5-♭6-♭7-1

In the scale of C natural minor, the 3rd, 6th, and 7th notes are flat (♭). This applies in both ascending and descending motions. In the given Audio example, these notes are indicated with accents.

C harmonic minor

C-D-E♭-F-G-A♭-B-C

1-2-♭3-4-5-♭6-♯7-1

In C harmonic minor, the 3rd and 6th notes are flat (♭). However, the 7th note is raised as it acts as a leading tone to the key note. It is usually marked with a sharp (♯) symbol. This applies in both ascending and descending motions. In the given Audio example, these notes are indicated with accents.

C melodic minor

(Ascending)

C-D-E♭-F-G-A-B-C

1-2-♭3-4-5-♯6-♯7-1

(Descending)

C-B♭-A♭-G-F-E♭-D-C

1-♭7-♭6-5-4-♭3-2-1

If we take a close look at the scale of C melodic minor, the ascending and descending motions have different notes. As previously explained, the 3rd note in a minor scale is always flat (♭). When ascending, the 6th and the 7th note are raised (♯). However, when descending, these notes are lowered (♭) back to its natural minor form. In the given Audio examples, these notes are indicated with accents.

N.B. All forms of minor scales have note 3 as flat (♭). In natural minor, notes 6 and 7 are flat (♭). In harmonic minor, note 6 is flat (♭) but note 7 is raised (♯). In melodic minor, notes 6 and 7 are raised (♯) when ascending, but lowered (♭) when descending.

Chord

A chord is basically a set of different pitches that sound well together. As discussed earlier, there are notes that complement and oppose one another. If all the notes within a scale are played at once, it would make a cacophony of sound. Thus, knowing which notes can be sounded simultaneously is another important skill of a musician.

The general rule here is that in order to prevent clashing notes, never mix adjacent notes together e.g., 1 and 2, 2 and 3, 3 and 4, etc. Of course, exceptions apply but this is a topic for another time. For now, assume that every chord needs three notes, i.e., a triad, so begin with any note, then skip the neighbouring note, select the 3rd note, skip the 4th note, and select the 5th note. This is illustrated in the following example.

C-D-E-F-G-A-B

1-2-3-4-5-6-7

This example is in the key of C major. We can create a chord from the 1st note C by skipping the 2nd note D. Then we will take the 3rd note E. We shall skip the 4th note F. Finally, we are going to pick the 5th note G. When these selected notes are played together, we have created a C-E-G (from notes 1-3-5) chord.

If we want to create another chord starting from the second note D, we can apply the same rule. Thus it will be a D-F-A (2-4-6) chord. In short, pick three notes and skip the notes in between. Nevertheless, we are not covering all the different types of triads/chords here.

A chord does not have to be played only from the lowest note; it can be played in any order as long as it has the right notes. For example, the chord of C major can be arranged in the following ways.

C-E-G | E-G-C | G-C-E

1-3-5 | 3-5-1 | 5-1-3

As per the given example, there are three possible ways to arrange the chord.

Arpeggio

Chords can be played easily by chordal instruments such as piano, organ, or guitar. However, not all musical instruments can make two different sounds at once. For example, on bowed strings it is difficult and impractical. For solo instruments such as woodwinds, brass, or the human voice, it is just impossible. However, we can still imply a chord by playing single notes. If we play the notes from any chord in succession, we would create an arpeggio, which literally means ‘like a harp’. Sometimes an arpeggio is also called a broken chord.

Conclusion

If language governs how we speak and communicate, scales dictate how we make music and express ourselves. Without scales, music does not make sense since by nature, human ears look for rational sound, i.e., harmony. Not knowing the scales will result in wrong notes and clashes; that is pure ignorance or incompetency from one who aspires to make music well. Here are the key takeaways from this lesson:

Musical pitches are divided into 12 notes and these notes can complement or antagonise one another.

There are two types of scales in Western music tradition: major and minor. And each scale is comprised of only 7 notes. In total, there are 24 keys to make music in, combining major and minor scales for all the 12 notes.

For major scales, the interval between 3rd and 4th, and 7th and 1st (octave) is a semitone.

For minor scales, the 3rd note is always flat. For natural minor, the 3rd, 6th, and 7th notes are always flat, both in ascending and descending motion. For harmonic minor, the 3rd and 6th notes are always flat, but the 7th note is always sharp, both in ascending and descending motion. For melodic minor, the 3rd is always flat, but the 6th and 7th notes are sharp when ascending and back to flat when descending.

Chords are a group of notes that sound well together. We need at least three notes to form a chord and they must not be adjacent to each other.

Arpeggios are a way to play chord notes separately.

Mastering the scales is a prerequisite to be a proficient musician. Sounds like a lot of work, but the good thing is the rules are similar to each other. The journey to musical mastery takes years, if not decades. Thus it is best to start practising now.

All you have to do is to touch the right key at the right time. - J.S. Bach